The Strategist’s Most Critical (and Overlooked) Skill

If you’ve ever built a software product, designed a user experience, or architectured a complex IT system that failed to land with its audience, you’ve likely experienced the sting of a universal truth: a brilliant solution to the wrong problem is a failure. Over the course of my nearly two decades of navigating the turbulent waters of digital product development, I’ve seen more projects derailed by poor problem definition than by any technical shortcoming.

We, as designers, architects, and strategists, are natural problem-solvers. Our instinct is to build. But that very instinct is our greatest Achilles’ heel. We jump to solutions, wireframes, architecture diagrams, and code repositories before we truly understand the landscape of the problem. We treat the symptom while the disease continues to rage.

The antidote to this is a disciplined, rigorous practice called Problem Framing. It is the single most powerful skill in a strategist’s arsenal. When you frame a problem correctly, you create a north star for your entire project. Every decision, from the technology stack to the UI micro-interactions, can be measured against this frame for coherence and relevance.

As Albrecht Enders and Arnaud Chevallier brilliantly argue in their book, “Solvable: A Simple Approach to Problem Solving,” a well-framed problem isn’t just a description of a headache; it’s the foundation of a solution with lasting impact. And one of the most effective ways to build this foundation is by tapping into a fundamental human technology: storytelling.

Why Storytelling? The Psychology of the Problem Frame

Human brains are wired for narrative. We understand the world through stories—they provide context, create empathy, and illuminate cause and effect. A dry, technical problem statement like “Q2 revenue is down 15% YoY” is a data point. It doesn’t inspire; it doesn’t guide; it doesn’t reveal a path forward.

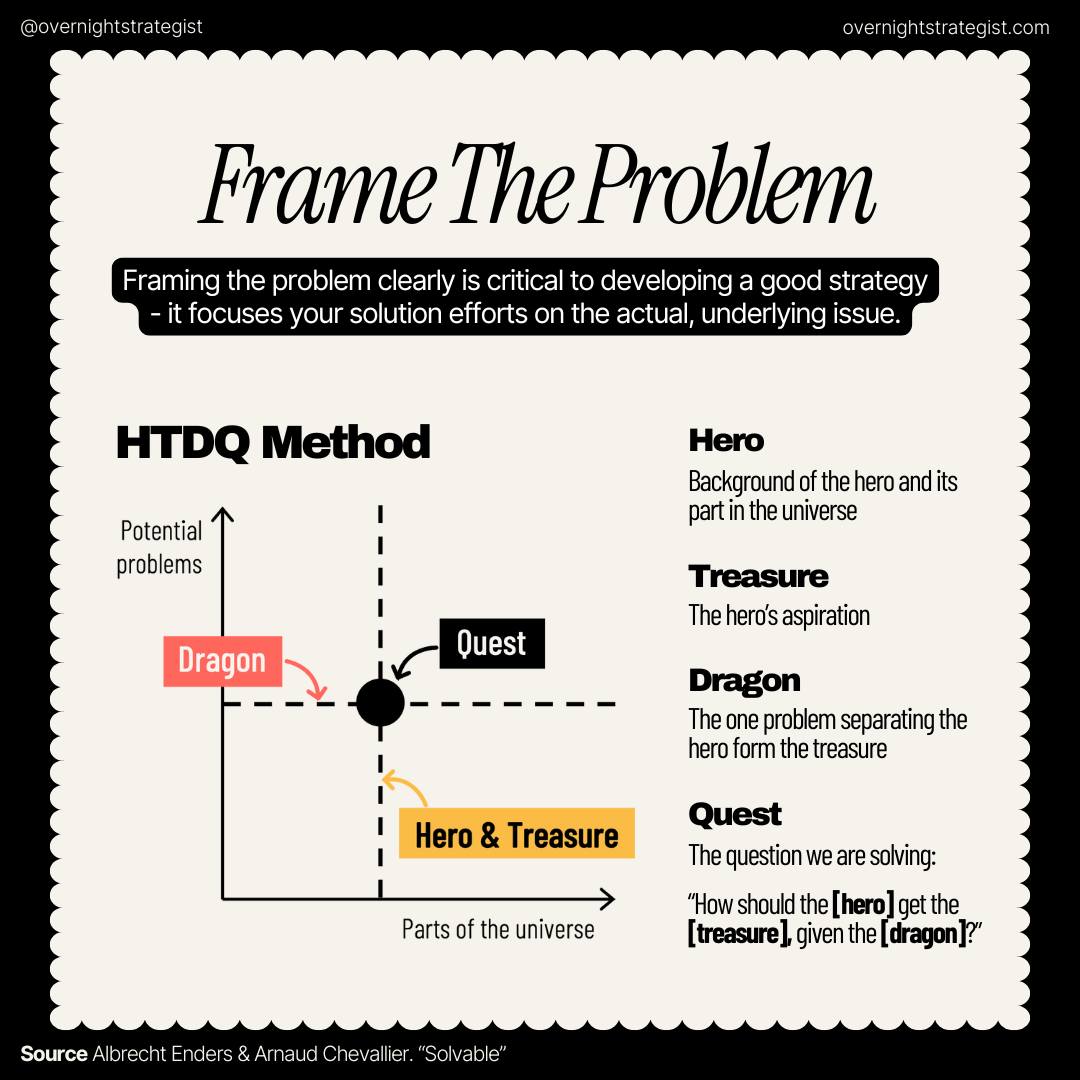

But a story does. By framing a problem within a narrative structure, we instantly make it more comprehensible, memorable, and actionable for everyone involved: stakeholders, developers, designers, and end-users. This is where the HTDQ Method (Hero, Treasure, Dragon, Quest) from “Solvable” becomes an indispensable tool in our toolkit.

Deconstructing the HTDQ Method: A Framework for Clarity

The HTDQ method forces us to move beyond the superficial and structure our problem discovery into a powerful, guiding question. Let’s break it down, not just as a theoretical concept, but as a practical process we can implement on Monday morning.

1. The Hero: Who Are We Designing For?

In any story, the hero is the protagonist. In problem framing, the Hero is not your company, your product, or your technology. The Hero is the user, the customer, the person whose problem we are solving. It is our job to understand them deeply.

Inputs: User personas, ethnographic research, interview transcripts, analytics data, stakeholder knowledge, journey maps.

Process: Go beyond demographics. Understand their background, their environment (“their universe”), their goals, their motivations, and their current pain points. What does a day in their life look like? What tools do they use? What do they value?

Output: A rich, empathetic description of the primary user. This is the anchor for everything that follows.

Best Practice: Avoid the “elastic user” (a persona so vague it can be stretched to fit any argument). Be specific. Use real quotes from user interviews to give the Hero a voice.

Example (from IT Architecture): The Hero isn’t “the database admin.” It’s “Maria, a senior DBA at a financial institution, who is responsible for ensuring 99.99% uptime for legacy systems while under pressure to migrate to cloud-native infrastructure, all while adhering to strict SEC compliance rules.” This level of detail changes everything.

2. The Treasure: What is the Hero’s True Aspiration?

The Treasure is the desired end state. It’s the “happily ever after.” It’s not a feature (“a mobile app”) but the ultimate value or outcome the Hero seeks. Often, stakeholders fixate on a specific solution (a Treasure they’ve imagined) without validating if it’s what the Hero truly needs.

Inputs: User goals from research, business objectives, value proposition canvases, desired outcomes.

Process: Ask “What does success look like for the Hero?” Use the “Five Whys” technique to dig past surface-level desires to uncover fundamental human needs: autonomy, competence, relatedness, time savings, reduced anxiety, etc.

Output: A clear, aspirational statement of the user’s goal, divorced from any specific solution.

Best Practice: Separate the user’s need (the Treasure) from the anticipated solution. The user’s need might be “to get across the river.” Their suggested solution is “a boat.” Your job is to discover if a bridge, a tunnel, or a ferry might be a better solution to that underlying need.

Example (from UX Design): For an e-commerce site, the Treasure isn’t “a one-click checkout.” That’s a solution. The Treasure is “to complete my purchase quickly and securely without any friction or anxiety about my payment details.” This reframing opens up a universe of solutions beyond just a button.

3. The Dragon: What is the Real Obstacle?

The Dragon is the problem, the villain, the obstacle standing squarely between the Hero and the Treasure. Crucially, it must be the primary obstacle. Many projects fail because they try to slay five dragons at once, resulting in a convoluted and ineffective solution. The HTDQ method demands focus.

Inputs: Pain points identified in user research, technical constraints, business constraints, competitive analysis, root cause analysis.

Process: This is where deep analysis is critical. Is the Dragon a technical debt? A user’s lack of knowledge? A flawed business process? A regulatory hurdle? Use techniques like root cause analysis (e.g., Fishbone Diagrams) to ensure you’re attacking the cause, not the symptom.

Output: A single, well-defined, and significant obstacle.

Best Practice: The Dragon should be a barrier that, if removed, would clear the most direct path for the Hero to reach the Treasure. Beware of “Dragon Blindness”—the tendency to see only the obstacles that are familiar to you (e.g., a developer seeing only technical dragons).

Example (from Software Development): The Dragon preventing users from adopting a new feature might not be its complexity (the symptom), but the fact that it’s not integrated into their daily workflow and thus is easily forgotten (the root cause). Slaying the “complexity” dragon is different from slaying the “lack of integration” dragon.

4. The Quest: The Overarching Question

The Quest is the culmination of the framing process. It synthesizes the Hero, Treasure, and Dragon into a single, strategic question that will guide your entire solutioning effort. It is the problem frame made manifest.

Formula: “How might we [help the Hero] [achieve the Treasure], despite [the Dragon]?”

Output: A single, focused, and actionable question that serves as the project’s thesis statement.

Best Practice: The Quest should be broad enough to allow for creative solutions but narrow enough to provide meaningful constraints. It should be displayed prominently on every project wall (physical or virtual) and used as a litmus test for every proposed feature, user story, or architectural decision: “Does this help us on our Quest?”

The HTDQ Method in Action: A Practical Case Study

Let’s move from theory to practice with an extended example.

Initial, Poorly Framed Problem: “We need an app for our local bookstore.”

This is a solution masquerading as a problem. It gives us no direction, no constraints, and no understanding of the real challenge.

Applying HTDQ:

The Hero: “Clara, the owner of ‘The Reading Nook,’ a small independent bookstore. She’s a literary expert with a passionate local customer base but is struggling to compete with the convenience and inventory of online giants. Her universe is one of community, personal touch, but limited capital and physical space.”

The Treasure: “To not just survive, but thrive by leveraging her unique advantages to build a sustainable business model that competes effectively on value, not just price.”

The Dragon: “The inability to match the vast inventory and instant, low-cost delivery offered by online retailers, which leads to customers ‘showrooming’—browsing in her store but buying online.”

The Quest: “How might we help Clara, the local bookstore owner, build a sustainable thriving business (Treasure), despite her inability to compete on inventory size and delivery speed (Dragon)?”

This Quest fundamentally changes the solution space. “Build an app” is now just one potential path. Our Quest forces us to explore Clara’s unique advantages: community, curation, and experience.

Potential solutions now become:

A subscription box service featuring curated local authors.

An “Expert Match” service where Clara personally recommends books based on a customer’s quiz.

Enhanced in-store events with online streaming and community forums.

A partnership with other local businesses to create a “Local Discovery” trail.

The technology (app, website, SaaS platform) becomes a servant to the strategy, not the strategy itself. This is the power of a well-framed Quest.

Essential Tools and Techniques for Effective Problem Framing

Framing isn’t a passive activity; it’s an active process of discovery and synthesis. Here are the tools and inputs I’ve relied on for years:

Empathy Maps & User Personas: To define the Hero. (Reference: Interaction Design Foundation on Personas)

Journey Mapping: To understand the Hero’s current universe and identify potential Dragons and Treasures. (Reference: Nielsen Norman Group on Journey Mapping)

The “Five Whys” Technique: To dig past symptoms and find the root cause Dragon and the true Treasure. (Reference: MindTools on the 5 Whys)

Stakeholder Interviews: To understand business constraints and aspirations, which often form part of the universe’s rules.

Competitive Analysis: To understand the landscape and identify common, yet unsolved, Dragons.

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) Diagrams: To visually map the causes of a problem and identify the core Dragon. (Reference: ASQ on Root Cause Analysis)

How Might We (HMW) Questions: The foundational technique for forming the Quest. (Reference: IDEO Design Kit)

Best Practices for the Master Craftsman

Step Back Before Diving In: Resist the urge to solve. Dedicate scheduled, solution-free time for pure problem discovery and framing.

Embrace Reframing: A frame is a hypothesis, not a decree. Test it. Challenge it. Ask your team, “What if the Dragon is actually something else?” Look at the problem from multiple angles—from the user’s perspective, the business’s perspective, the technical perspective.

Make it a Team Sport: Problem framing cannot be done in a silo. Include developers, designers, marketers, and support staff. Their diverse viewpoints will reveal facets of the problem you cannot see alone.

Time-box the Framing Phase: While crucial, framing can become an endless cycle of analysis paralysis. Set a deadline. The Quest can and should evolve, but it needs to be established firmly enough to guide the next phase of work.

Conclusion: Your Quest Awaits

Framing the problem is the highest-leverage activity in any strategic endeavor. It is the art of asking the right question before desperately searching for answers. The HTDQ method provides a memorable, robust, and human-centered framework to master this art.

By defining our Hero, Treasure, and Dragon, we craft a Quest that aligns teams, inspires creativity, and ensures that the solutions we build—whether a elegant UX flow or a resilient IT architecture—are not just technically sound, but meaningfully impactful. Remember the old adage, now imbued with new meaning: A well-framed problem is half-solved.

Your next project is a story waiting to be written. Start by framing the narrative.

Image credits: OverNightStrategist