From Raw Insights to Persuasive Action

As a UX Designer and IT Solutions Architect with over two decades in the trenches, I’ve seen countless “strategies” gather digital dust. These documents are often beautiful, filled with jargon, charts, and ambitious goals. Yet, they fail to inspire action. They fail to change behavior. They fail, ultimately, because they are not strategic in the most fundamental sense.

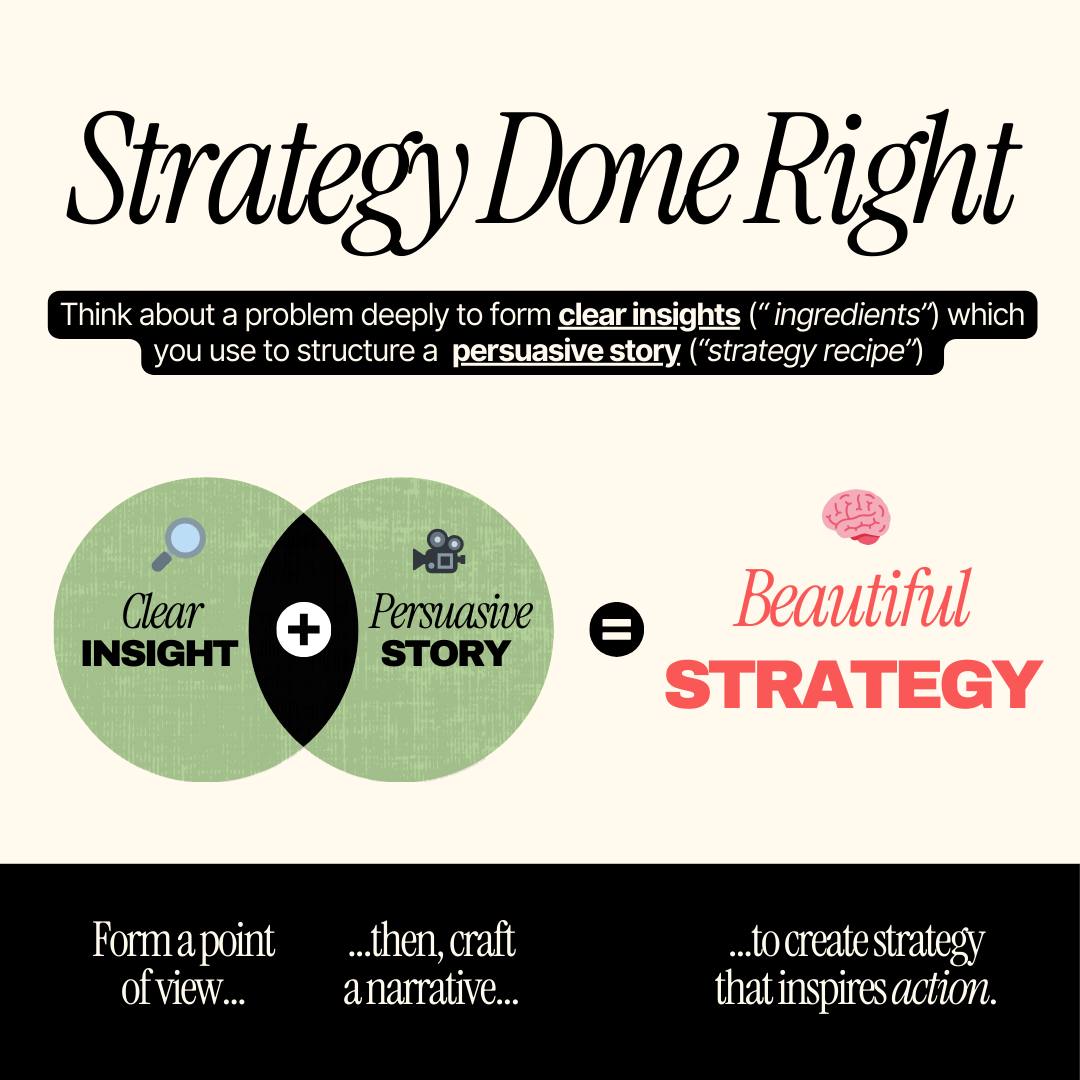

The problem isn’t a lack of effort; it’s a misunderstanding of what strategy truly is. Strategy is not a plan. A plan is a list of steps. Strategy is the compelling story that explains why those steps are necessary and how they lead to victory. It is the bridge between the current reality and a desired future.

The framework in the provided image encapsulates this perfectly: Beautiful Strategy emerges from the alchemy of Clear Insights and a Persuasive Story. Think of insights as your raw “ingredients” and the story as your “strategy recipe.”

In this article, we will deconstruct this elegant model. We’ll dive deep into the crafts of insight formation and story crafting, translating abstract concepts into a practical toolkit for designers, architects, product managers, and leaders. We’ll explore the necessary inputs, the mental models, the frameworks, and the expected outputs that transform a vague notion into a strategy that gets done right.

1: The “Ingredients” – The Art and Science of Forming Clear Insights

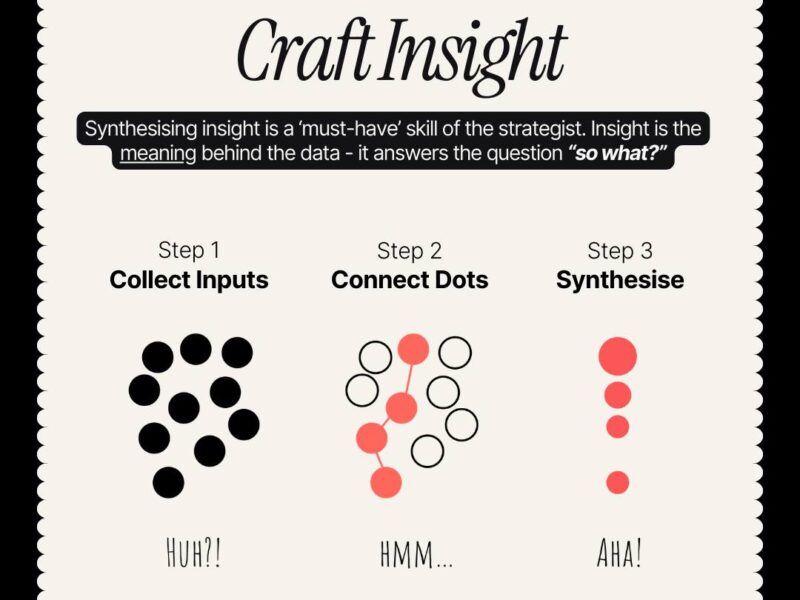

An insight is not a fact. A fact is “website traffic dropped by 15% last quarter.” An insight is the deeper understanding of why it happened and what it means. It’s the “aha!” moment that reveals a hidden truth, a non-obvious connection, or a fundamental human need. Insights are the foundation because a strategy built on superficial facts is a house built on sand.

What Constitutes a “Clear Insight”?

A clear insight has three key characteristics:

Human-Centered: It speaks to a core motivation, pain point, or desire of the people you are designing for (users, customers, stakeholders). It often uses emotional language.

Non-Oblivious: It goes beyond surface-level observations to reveal something new or previously unarticulated.

Actionable: It clearly implies a direction or opportunity. It points toward a “what if?” or “we should.”

Weak Observation: “Users abandon their shopping cart on the payment page.”

Clear Insight: “Users feel a moment of ‘sticker shock’ and anxiety about financial security when they are forced to create an account before seeing the full cost with shipping and taxes. The perceived barrier to abandonment is low because they haven’t yet committed mentally.”

The second statement is rich, human, and immediately suggests potential solutions (e.g., guest checkout, show all costs upfront).

Necessary Inputs for Insight Generation

You cannot synthesize insights from a vacuum. You need raw material. As an architect, I never design a system without first gathering extensive requirements. Similarly, strategic insights require disciplined input collection.

Qualitative Data: This is the bedrock of human understanding.

User Interviews: One-on-one conversations to explore motivations, behaviors, and frustrations in depth. (Tools: Otter.ai for transcription, Dovetail for analysis).

Contextual Inquiry: Observing users in their natural environment (whether a physical office or using a software tool) to see what they actually do versus what they say they do.

Support Tickets & Sales Call Logs: A goldmine of recurring problems and unmet needs.

Quantitative Data: This provides the “what” and “how much” to complement the qualitative “why.”

Analytics: (Google Analytics, Adobe Analytics, Hotjar) to see behavioral patterns at scale—drop-off points, popular features, navigation paths.

Survey Data: (SurveyMonkey, Typeform) to gather attitudinal data from a broader audience.

Product Usage Data: (Mixpanel, Amplitude, Pendo) to understand feature adoption and engagement metrics.

Market and Business Context:

Competitive Analysis: Understanding the landscape of alternatives available to your users.

Business Goals & KPIs: The strategic objectives of the organization. Your insights must ultimately connect to these.

Technical Capabilities & Constraints: The reality of your current architecture, tech stack, and resources.

The Process: Synthesizing Raw Input into Clear Insights

This is the “deep thinking” part. It’s messy, iterative, and requires moving from a wide lens to a narrow focus.

Aggregate & Immerse: Gather all your inputs in one place. Tools like Miro or Mural are invaluable for creating digital “war rooms” where you can dump interview notes, analytics screenshots, and quotes.

Affinity Mapping: This is the primary synthesis technique. Write individual data points, observations, and quotes on digital sticky notes. Then, silently and collaboratively, group them based on natural relationships. The groups that emerge are themes. The goal is to move from 200 individual notes to 5-7 core themes. This is where you “connect the dots.”

Uncover the “Why” with the 5 Whys: For each key theme or problem, ask “why” iteratively. Why are users abandoning the cart? Because they have to create an account. Why is that a problem? Because it adds friction before they see the final cost. Why is that important? Because they are wary of hidden fees and aren’t yet committed to the purchase. This drilling down reveals root causes, not symptoms.

Frame as Insights: For each key theme, craft a clear, concise insight statement. A useful framework is the “[User] needs to [verb] because [surprising motivation/constraint]” model. For example: “First-time visitors need to verify the total cost effortlessly because they distrust hidden fees and have a low commitment threshold at this stage in their journey.“

Recommended Frameworks for Insight Generation

Jobs-to-Be-Done (JTBD): This framework posits that users “hire” products to get a “job” done. The deep insight isn’t about the user’s demographics but about the progress they are trying to make in a given situation. It’s a powerful way to avoid building features and instead focus on solving core problems. (Reference: The Theory of Jobs to Be Done)

Mental Models: Indi Young’s work on mental models involves mapping the user’s thought process and tasks against the system you are providing. The gaps between the user’s model and the system’s model are where the deepest insights—and frustrations—lie. (Reference: Mental Models by Indi Young)

Expected Outputs of the Insight Phase

You should not exit this phase with a 100-page report. The output is a set of sharp, resonant artifacts that capture your collective understanding:

A Set of Prioritized Insight Statements: Clear, actionable truths about your users and the context.

Journey Maps: Visualizations of the user’s end-to-end experience, highlighting key pain points and moments of truth identified through your insights.

Personas (if useful): Archetypes based on behaviors and goals, not demographics, grounded in the synthesized data.

A Point of View (POV) Statement: A consolidated summary that defines the challenge from the user’s perspective. (Example: “How might we help first-time visitors feel confident and secure about their purchase before asking for a commitment?”)

2: The “Recipe” – Crafting a Persuasive Story

Having a pile of exquisite ingredients doesn’t mean you have a meal. The insights are inert until they are woven into a narrative that compels people to act. This is where strategy lives or dies. As a solutions architect, I don’t present a list of server specifications; I tell a story about system resilience, scalability, and future-proofing that aligns with the CTO’s vision.

A persuasive story provides meaning, context, and order. It answers the most critical questions: Why should we care? Why now? What do we do? What happens if we don’t?

The Anatomy of a Strategic Narrative

The most effective strategic stories follow a classic arc, much like a film or novel. This structure is neurologically comforting and persuasive.

The Hook & The Challenge (Act I: The Past & Present): This is your introduction. It must start with a shared reality, often anchored by a key insight. “Remember our goal to increase market share? Well, our analytics show we’re bleeding first-time customers. Our research reveals why: at the most critical moment of trust-building, we’re asking for a leap of faith instead of offering transparency.” You are setting the stage, defining the problem in a way that is undeniable and tied to business goals.

The Journey & The Solution (Act II: The Future Vision): This is the core of your strategy. Here, you paint a vivid picture of the future world once the problem is solved. You introduce your central strategic idea—the “big bet.” “Imagine a world where a new visitor arrives on our site, adds a product, and immediately sees the total cost, including shipping, with a single click. They can check out as a guest in seconds. The anxiety is gone. The trust is built.” You are selling the destination, not the flight path. Use conceptual diagrams, storyboards, or prototypes to make this vision tangible. This is where you connect your solution back to the insights: “This directly addresses the core insight that users need cost certainty before commitment.”

The Resolution & The Action Plan (Act III: The Path Forward): This is where you bridge the vision to reality. A vision without a plan is a hallucination. You provide the logical, sequenced steps. *”To make this real, we will execute a three-phase plan: Phase 1: Implement a guest checkout system. Phase 2: Revamp the cart to calculate shipping in real-time. Phase 3: Launch a trust signal program.”* This section must be specific, but it’s still a strategic roadmap, not a project plan. It answers “What?” and “Why?” before the detailed “How?”

Necessary Inputs for Story Crafting

The primary input is your output from Part 1: the Clear Insights. You also need:

Stakeholder Map: An understanding of who you are presenting to, their personal motivations, and their concerns.

Business Objectives: The story must clearly demonstrate how the strategy achieves business goals (e.g., increase conversion, reduce support costs, enter a new market).

Constraints: Acknowledging technical, budgetary, or timeline constraints within the story builds credibility.

The Process: Structuring the Narrative

Start with the Ending: Know your key recommendation first. What is the one thing you want the audience to remember and approve?

Map the Narrative Arc: Use a storyboarding technique. Sketch out the key scenes: the problem, the moment of insight, the vision of the future, the path to get there.

Weave in Evidence: Place your insights and data points strategically throughout the story to support each beat. Don’t present a “data dump” slide; let a key statistic reinforce a point in the narrative. “75% of users who abandon at the cart cite ‘unexpected costs’ as the reason—this is the pain we are solving.”

Create Visual Anchors: Humans are visual creatures. Replace bullet points with diagrams, journey maps, and concept screens. A tool like Figma or Sketch is perfect for creating clean, compelling visuals for your story.

Recommended Frameworks for Persuasive Storytelling

Nancy Duarte’s “What Is, What Could Be”: In her seminal book Resonate, Duarte outlines a powerful pattern. She contrasts the current state (“what is”) with the future ideal state (“what could be”) throughout the presentation, creating a rhythmic persuasion that culminates in a call to action. This is perfectly suited for strategic pitches. (Reference: Duarte – Resonate)

Simon Sinek’s “Start With Why”: Begin your story not with what you are proposing, but why it matters. The “why” is the belief, the purpose, the cause. This connects to the audience’s limbic brain, the source of emotion and decision-making. Your insights often point directly to the “why.” (Reference: Simon Sinek – Start With Why)

The Hero’s Journey: Frame the story so that the customer is the hero, not your company. Your product or strategy is the “aid” or “tool” that helps the hero overcome challenges and achieve their goal. This creates powerful empathy.

Expected Outputs of the Story Phase

The output is not just a document; it is an experience.

A Strategic Narrative Deck: A slide presentation designed to be presented, not read. It is visual, sparse on text, and follows the story arc. It is the primary communication tool.

A Vision Video or Prototype: An interactive Figma prototype or a short animation that brings the future experience to life. This is incredibly effective for creating shared understanding.

A High-Level Roadmap: A visual timeline that outlines the key initiatives (Epics, Themes) derived from the strategy, sequenced logically. (Tools: Aha!, Productboard, or a simple Miro board).

3: The Alchemy – Where Insight and Story Combine into Beautiful Strategy

A “Beautiful Strategy,” as the image states, inspires action. It is elegant because it is simple to understand but deep in its foundation. It feels inevitable because the logic flows seamlessly from the problem through to the solution.

In my work, this is the difference between a technical specification that is approved and one that is championed. The championed strategy is the one that everyone from the CEO to the junior developer can understand, believe in, and see their role in executing.

Best Practices for the Integrated Process

Iterate, Don’t Waterfall: Insight generation and story crafting are not linear phases. As you start to craft the story, you will find gaps in your insights. Go back and do more research. It’s a loop.

Co-create with Cross-Functional Teams: Include engineers, marketers, and support staff in both the insight synthesis and story-building sessions. Their diverse perspectives will strengthen both the insights and the buy-in.

Kill Your Darlings: Be ruthless in prioritizing. A strategy that tries to solve every problem solves none. Focus on the few insights that matter most and build a simple, powerful story around them.

Practice Empathy for Your Audience: When crafting the story, your primary user is the decision-maker in the room. What keeps them up at night? Tailor the narrative to their goals and language.

A Concrete Example: Re-architecting a Legacy System

Let’s apply this to a classic IT challenge.

Insight Phase:

Inputs: Developer interviews (frustration with outdated code), performance metrics (slow load times causing revenue loss), business goals (need to launch new features faster), competitive analysis (rivals have more agile platforms).

Synthesis: Affinity mapping reveals a core theme: “Fear and Inertia.” The business fears the cost and risk of a migration. Developers fear the complexity. The clear insight: “The organization is trapped in a cycle of incremental fixes on a fragile foundation, which is silently costing us market agility and developer morale.”

Story Phase:

The Hook (Challenge): “Our competitors can launch new features in weeks; it takes us months. Every time we touch our core platform, we risk a catastrophic failure. We are on a technical treadmill, running fast just to stay in place.” (Supported by metrics on deployment frequency and incident reports).

The Journey (Solution): “Imagine a future where our platform is a set of modular, scalable services. A future where a developer can deploy a new payment feature with confidence in hours, not months. This isn’t just a tech upgrade; it’s a transformation of our ability to compete.” (Supported by architecture diagrams and a vision prototype).

The Resolution (Action): “We will achieve this through a phased strangler fig pattern, gradually replacing parts of the old system without a risky ‘big bang’ cutover. Phase 1: Isolate the database. Phase 2: Build a new API layer for new features. This minimizes risk and delivers value at every step.” (Supported by a high-level roadmap).

This story, grounded in deep insights about both technical and human constraints, is far more persuasive than a proposal that simply says: “We need to migrate from .NET Framework to .NET Core.”

Conclusion: Strategy as a Craft

Strategy done right is not a mystical art reserved for top-tier consultants. It is a disciplined craft. It is the hard work of diving deep into the data and human experience to find clear insights—the true ingredients. It is the creative work of weaving those insights into a persuasive story—the recipe—that provides clarity, creates alignment, and, most importantly, inspires the entire team to move from understanding to action.

By mastering these two complementary skills, you stop creating documents that are filed away and start creating strategies that are executed. You move from being an order-taker to a trusted advisor. You build not just products and systems, but the consensus and conviction needed to make them successful.

Further Reading & References:

On Strategy: Good Strategy / Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters by Richard Rumelt.

On Insight & User Research: Just Enough Research by Erika Hall.

On Storytelling: Resonate: Present Visual Stories that Transform Audiences by Nancy Duarte.

On JTBD: The Jobs to Be Done Playbook by Strategyzer.

On Systems Thinking: Thinking in Systems: A Primer by Donella H. Meadows.

Image belongs to: Overnight Strategist.